What we talk about when we talk about influence functions: Part 1

Published:

What we talk about when we talk about influence functions: Part 1

Efficient influence function vs. empirical influence function: a visual disambiguation

I spent a few weeks last year confused about influence functions. The main source of the confusion was that influence functions manifest as distinct objects in multiple fields: the efficient influence function (EIF) in semiparametric statistics and the empirical influence function (EmpIF) in robust statistics and, more recently, ML interpretability.

While these objects are conceptually related, they are used for different purposes and often require specialized implementations.

Both objects measure the sensitivity of an estimand to changes in some underlying distribution. They are concepts defined in relation to an estimand, a finite-dimensional functional \(\Psi(P)\) of a distribution \(P\).

In this Part 1 of a three-part series on influence functions, we will work with the mean estimand, i.e., \(\Psi(P) \equiv \mathbb{E}_P[X]\). We will derive the EIF of this estimand and show that, when \(P\) equals the empirical distribution \(P_n\), the EIF and EmpIF coincide.

Deriving the efficient influence function for the mean

Let us start by deriving the EIF for the mean estimand, \(\Psi(P) = \mathbb{E}_P[X]\). We will use a simple method that works in most cases, formalized by Ichimura and Newey (2015). See Hines et al. (2022) for a very friendly tutorial. In brief, the method is based on the result that the EIF is what’s called a Gateaux derivative (a type of generalized derivative for probability distributions) with respect to a smooth perturbation evaluated at a point mass. It works by first defining what’s called a \(\delta\)-contaminated distribution, which is the result of perturbing a distribution with a point mass at \(x\) with weight \(\epsilon\): \[P_\epsilon = (1-\epsilon)P + \epsilon \delta_x.\] The EIF can then be derived as the following generalized derivative: \[{\rm EIF} \equiv \psi(x; P, \Psi) = \lim_{\epsilon \to 0} \frac{\Psi(P_\epsilon) - \Psi(P)}{\epsilon}. \tag{1}\]

Applying this to \(\Psi(P) = \mathbb{E}_P[X]\), we have \[\Psi(P_\epsilon) = \Psi(P) - \epsilon \Psi(P) + \epsilon x,\] so the expression in the limit of \((1)\) yields \[\frac{\Psi(P) - \epsilon \Psi(P) + \epsilon x - \Psi(P)}{\epsilon} = -\Psi(P) + x.\]

So we simply have \[\psi(x; P, \Psi) = -\mathbb{E}_P[X] + x.\]

The empirical counterpart

The EmpIF, on the other hand, is commonly defined via a leave-one-out (LOO) formulation with respect to the empirical measure, \[P_n \equiv \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \delta_{x_i}.\] The estimand of interest, then, is simply the sample mean: \[\Psi(P_n) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n x_i.\] The EmpIF asks what the effect on \(\Psi\) would be if a sample \(x_j\) were to be removed. Denoting by \(P_n^{-j}\) the distribution without \(x_j\), the sample mean under perturbation would be: \[\Psi(P_n^{-j}) = \frac{1}{n-1} \sum_{i\neq j} x_i.\] Then the EmpIF with appropriate scaling is \[{\rm EmpIF} = \psi_{\rm emp}(x_j; \Psi) = (n-1)\left(\Psi(P_n) - \Psi(P_n^{-j})\right),\] where the notation no longer explicitly includes the dependence on the distribution, as the distribution is always assumed to be \(P_n\).

Notice that, putting \(\bar X \equiv \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n x_i\), this can be written \[\psi_{\rm emp}(x_j; \Psi) = (n-1) \left( {\bar X} - \frac{1}{n-1} \sum_{i \neq j} x_j \right) = (n-1){\bar X} - \left( n{\bar X} - x_j \right) = -{\bar X} + x_j,\] or, equivalently, \(\psi_{\rm emp}(x; \Psi) = -\mathbb{E}_{P_n}[X] + x.\) We have shown that the EIF with \(P=P_n\) equals the EmpIF when the estimand \(\Psi\) is the mean, i.e., \(\psi(x; P_n, \Psi) = -\mathbb{E}_{P_n}[X] + x = \psi_{\rm emp}(x; \Psi).\)

Numerical verification

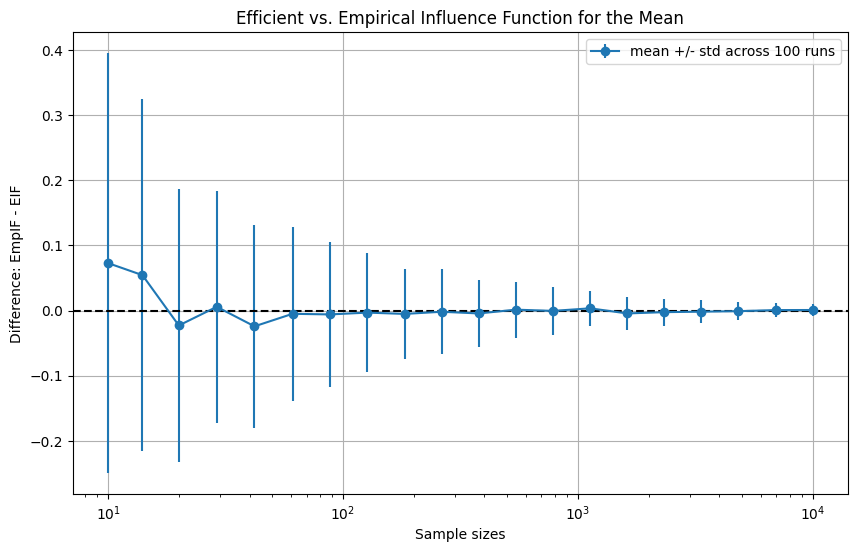

The EmpIF approaches the EIF as \(n\) increases. Let’s verify this visually, though it should be obvious as we are basically just checking that the sample mean of a standard normal approaches 0.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

np.random.seed(42)

# Define true distribution as a standard normal

def get_eif(x):

return 0.0 - x # true mean is 0

def get_empif(x, all_x):

return all_x.mean() - x

diff = []

diff_sigma = []

sample_sizes = np.logspace(1, 4, 20).astype(int)

for n_emp in sample_sizes:

diff_n = []

for _ in range(100): # repeat 100 times

# Define some empirical distribution

X = np.random.normal(size=n_emp)

# Choose x_j

x_j = np.random.choice(X)

# Evaluate EIF, EmpIF

eif = get_eif(x_j)

empif = get_empif(x_j, X)

# Get difference

diff_n.append(empif - eif)

# Get mean, std in diff across runs

diff.append(np.mean(diff_n))

diff_sigma.append(np.std(diff_n))

# Verify that the two influence functions coincide

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.errorbar(sample_sizes, diff, yerr=diff_sigma, marker="o", label="mean +/- std across 100 runs")

plt.axhline(0, linestyle="--", color="k")

plt.xlabel("Sample sizes")

plt.ylabel("Difference: EmpIF - EIF")

plt.title("Efficient vs. Empirical Influence Function for the Mean")

plt.grid(True)

plt.legend()

plt.xscale("log")

This snippet produces

Summary

- We learned how to derive the EIF using the example of the mean estimand.

- We showed that, for the mean estimand, the EIF with \(P=P_n\) reduces to the EmpIF.

- We numerically confirmed this for varying \(n\).

While the mean example may appear trivial, the story is not as neat for other estimators, for which the use cases of EIF and EmpIF diverge. A sneak peek into the rest of the series:

Part 2. For more complex estimands, the EIF and EmpIF do not coincide in finite samples as they do for the mean estimand. We take a close look at the quantile estimand as an example of a non-linear functional. Because evaluating the EmpIF for every leave-one-out training sample can be unfeasible for estimators that involve model fitting, like the weights of a neural network, some approximations are commonly employed for ML interpretability.

Part 3. Fundamentally, the EmpIF is defined explicitly for \(P_n\) and estimates the finite-sample sensitivity of the estimand to particular data points. The estimand considered for the EmpIF is usually some (finite-dimensional) parameter of a parametric model. The EIF, on the other hand, is an idealized object, defined for an arbitrary distribution \(P\) without explicit reference to a parametric model, and representing the theoretical sensitivity of any estimand to infinitesimal perturbations on \(P\). Techniques like one-step estimation and targeted learning use the EIF to equip a potentially biased estimator with asymptotic efficiency.

References

[1] Ichimura, H., & Newey, W. K. (2015). The influence function of semiparametric estimators. Quantitative Economics, 13(1), 29-61. [2] Hines, O., Dukes, O., Diaz-Ordaz, K., & Vansteelandt, S. (2022). Demystifying statistical learning based on efficient influence functions. The American Statistician, 76(3), 292-304.